The legacy of colonialism in African poverty photography

Photography arrived in South Africa in 1846. Just seven years after its invention in Europe. Jules Leger set up his camera in Port Elizabeth and began creating a visual legacy that still shapes how we see Africa today.

This wasn’t accident. It wasn’t neutral technology spreading naturally across continents.

Photography entered Africa as a colonial weapon.

How colonial narratives shaped early visual representations

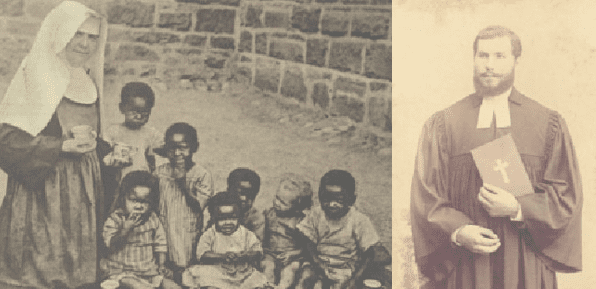

The camera became a tool of power long before anyone called it art. Missionaries, anthropologists, explorers, and traders spread photography throughout the interior. They created archives that served specific agendas, not objective truth. See this interview. “Saintly Sights – Pre 1900s Missionary Photography in South Africa – An Interview.”

Missionary photographs played a particularly clever dual role:

- Garnering support for colonial missions back in Europe

- Establishing racial hierarchies that justified their presence

Here’s how these early photographers constructed their version of Africa:

- Portraying African lands as “barren” and “uncivilised” – justifying resource allocation to European settlers

- Creating before-and-after narratives – traditional African clothing versus European dress as “progress”

- Deliberately omitting industrialised Africans – despite over 100,000 Africans working in South African mines by the early 20th century

- Focusing overwhelmingly on tribal imagery – whilst presenting Europeans in diverse, complex contexts

The colonial camera didn’t document reality. It constructed one.

Pictures of ivory caravans and rubber production once symbolised economic success. Today we recognise them as evidence of exploitation and harsh labour practises. Photographs of chained prisoners, originally symbols of colonial control, now reveal African resistance to abusive systems.

Photography’s contradictory power emerged when the same medium that promoted colonialism helped bring down King Léopold’s regime in the Congo Free State. Humanitarian campaigns recognised the visual image’s potential to influence public opinion. They distributed photographs of prisoners and mutilations as evidence of colonial abuses.

The camera could both create and destroy narratives of power.

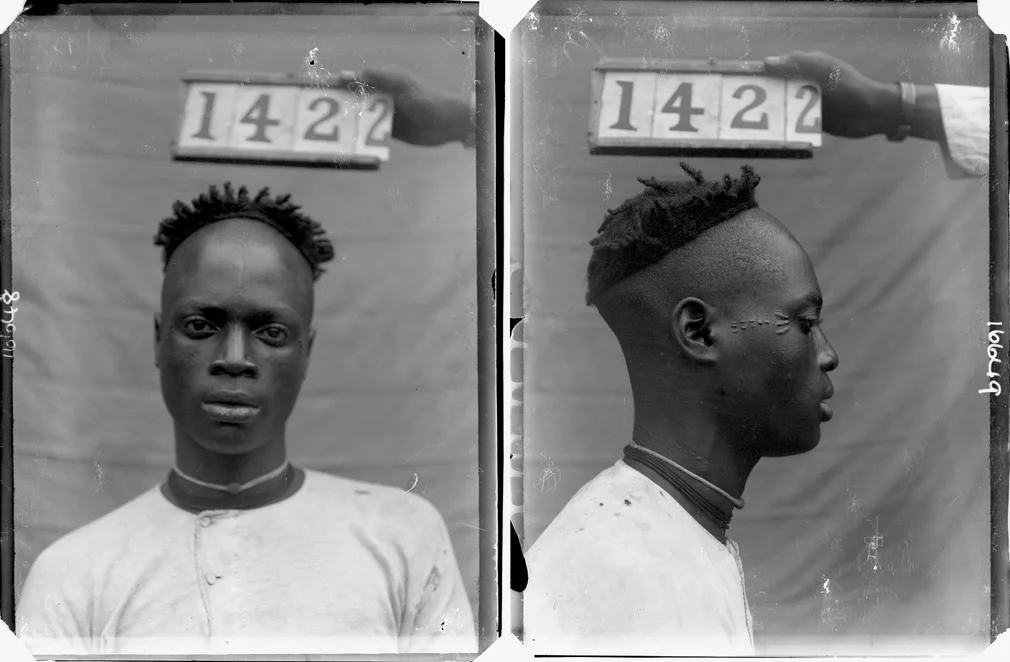

The role of anthropology and racial theory in image framing

Anthropologists wielded tremendous influence over African visual representation. Racist European theories were given false credibility through photography.

The Journal of the Anthropological Institute declared in 1896 that photography provided “facts about which there can be no question.” This supposed objectivity legitimised racial hierarchies that served colonial interests.

R.G. Seligman exemplified this approach. He applied social Darwinism and racial determinism to African ethnography. Seligman mentored influential anthropologist E. Evans-Pritchard and championed the Hamitic Hypothesis—the theory that all “civilisation” on the African continent came from a “superior” race of “Europeans” belonging to “the same great branch of mankind as the Whites.”

These photographers captured:

- Facial features and skull structures as “evidence” of European superiority

- Artificial boundaries around societies and ethnic groups

- Static, primitive representations that denied African complexity and change

Alfred Martin Cronin photographed in South Africa from 1904 to 1965. His motivation reveals the colonial mindset: “year by year the Natives were becoming more civilised, and any delay in the work would mean that valuable records of the Natives in their primitive state would be lost for all time.”

Cronin preserved not objective reality but colonial fantasy.

These early photographic practises continue influencing contemporary poverty photography. The tendency to decontextualise, exoticise, and present African subjects primarily through their suffering has deep colonial roots.

Understanding this history matters. It’s essential for creating ethical visual representations and critically analysing the poverty images that circulate globally today.

Leave a Reply