To reduce maternal mortality in Africa remains a crisis we cannot solve by focusing on women alone. The statistics tell a stark story – studies from Ethiopia and Kenya show male involvement in maternal care at only 38.2% and 18% respectively. These numbers reflect decades of interventions that miss a crucial reality. “Men’s Participation in Maternal Healthcare in Africa is a Win-Win for All” is by Dr. Azuka Ezeike, MBBS, FWACS (Obstetrics and Gynaecology), MSc (Public Health). Find details of the study here.

I’m Trevor Davies, and I’ve been working in this field long enough to see how men shape every maternal health decision across African households. They control the money. They make the choices about healthcare access. Their support can mean the difference between life and death for expectant mothers.

Yet cultural barriers keep fathers on the sidelines. Many still see pregnancy as “women’s business” and stay away from antenatal care. Economic pressures add another layer of complexity. The lack of awareness about their vital role creates gaps that cost lives.

You’re about to discover what really works to engage men in maternal health. I’ll share strategies that bring fathers into the conversation, address the cultural forces keeping them away, and highlight interventions that are changing how African men think about fatherhood and maternal care.

The path to reducing maternal mortality runs through engaging the men who hold the power to change outcomes. Let’s explore how to make that happen.

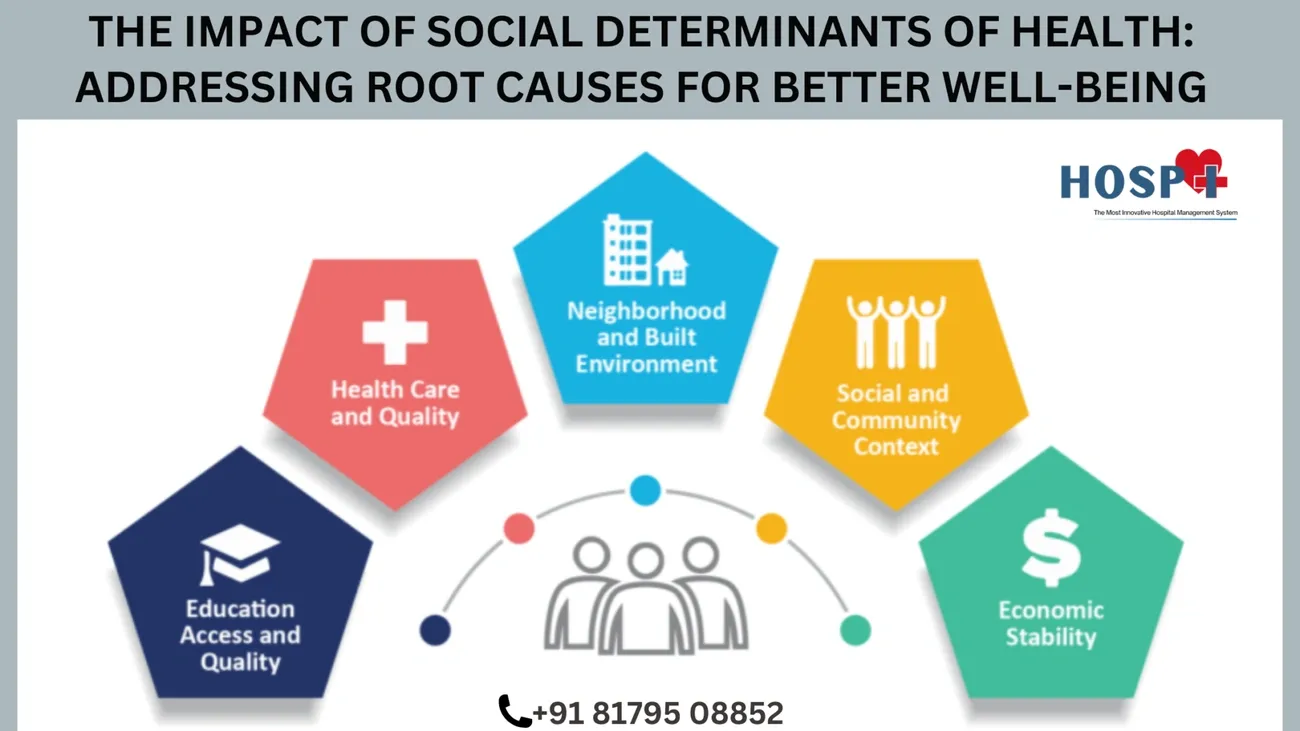

Understanding the root causes of maternal mortality

Image Source: hospital & lab management software

Maternal mortality tells two stories. The medical story focuses on bleeding, infections, and complications. The social story reveals who gets to make decisions about seeking help.

Both stories matter. But only one gets the attention it deserves.

Medical vs. social determinants

The medical facts are clear enough:

- Haemorrhage causes 34% of maternal deaths [1]

- Infections account for 10% [1]

- Hypertensive disorders create 9% of fatalities [1]

- Obstructed labour contributes 4% [1]

- Indirect causes from pre-existing conditions add another 20% [1]

These numbers tell us what kills mothers. They don’t tell us why some mothers get help in time and others don’t.

Here’s where the social story becomes crucial. MMR stands at 346 per 100,000 live births in low-income countries compared to 10 per 100,000 in wealthy nations [13]. The gap isn’t about medical knowledge. It’s about who can access that knowledge when it matters.

Poverty shapes every maternal health decision. Countries with stronger economies consistently show lower maternal mortality rates [12]. Women in poor countries face a 1 in 66 lifetime risk of maternal death compared to 1 in 7,933 in high-income countries [13].

Education creates another divide. Moving just 1% more women into primary education could prevent 5-8 maternal deaths per 100,000 births [1]. Notably, women’s education – not men’s – drives these improvements [1].

Health systems often fail when mothers need them most. In Togo, 33% of people live more than 5km from health facilities. They have just 0.22 ambulances per facility [2]. Conflict makes everything worse – maternal mortality jumps to 504 deaths per 100,000 births in war zones compared to 99 in peaceful areas [13].

Gender inequality underlies many of these failures. Across sub-Saharan Africa, discrimination against women correlates directly with higher maternal death rates [12]. This shows up as restricted autonomy, limited decision-making power, and cultural acceptance of female subordination [2].

Why focusing only on women isn’t enough

Traditional approaches miss a fundamental reality. Women don’t always control their own healthcare decisions.

Material dependency puts many women at the mercy of male relatives for healthcare access [14]. When men control household money, women face delays even in emergencies [2]. Studies in Togo identified partner neglect as a major cause of maternal deaths [14]. Many women report lacking basic support during pregnancy and childbirth [14].

The permission system creates deadly bottlenecks. Women must ask husbands for money, transport, and approval to seek care [12]. Without male support, accessing maternal services becomes virtually impossible.

These barriers multiply when they combine. A poor, uneducated woman from a marginalised ethnic group faces compounded obstacles [14]. She navigates not just medical needs but complex social relationships that control her access to life-saving care.

Gender roles make things worse. Rigid expectations about men’s and women’s responsibilities leave fathers disconnected from childcare [2]. This affects not just maternal health but children’s wellbeing when mothers die from preventable complications.

The tools to prevent maternal deaths already exist [14]. Medical knowledge isn’t the problem. Social barriers are. Until we address the power relationships that shape healthcare access – particularly men’s role in maternal health decisions – progress will continue to stagnate.

This is why engaging men matters so much. They hold keys that unlock access to care.

The invisible role of men in maternal outcomes

“Men in developing countries are the chief decision-makers, determining women’s access to maternal health services and influencing their health outcomes.”

— BMJ Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health (systematic review authors), Peer-reviewed systematic review, authoritative in public health research

Image Source: DatelineHealth Africa

“Men in developing countries are the chief decision-makers, determining women’s access to maternal health services and influencing their health outcomes.”

— BMJ Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health (systematic review authors), Peer-reviewed systematic review, authoritative in public health research

Every maternal death statistic hides a household story. Behind each number lies a web of decisions, permissions, and power dynamics that determine whether a pregnant woman receives care when she needs it most.

Men across sub-Saharan Africa serve as healthcare gatekeepers, yet their influence remains largely invisible to formal health systems. Socially constructed gender norms create uneven power structures between men and women, restricting women’s autonomy in decisions about their own maternal health [14]. This power imbalance shapes every aspect of care-seeking behaviour.

How men influence care-seeking decisions

The decision-making process follows predictable patterns across African communities. Men often consult soothsayers for preliminary diagnosis and advice about maternal health actions before women can seek medical attention [4]. These traditional consultations create dangerous delays in emergency obstetric care, as women must wait for rituals to be completed before receiving permission to access healthcare.

Women who try to make independent health decisions face serious consequences. Those who seek care without male approval are considered disrespectful because such actions disrupt social hierarchy and challenge established power structures [4]. Many women hesitate to seek care without explicit approval, even during emergencies.

Yet men’s influence can work both ways. When channelled constructively, male partner involvement results in better antenatal and postnatal care attendance, more hospital deliveries, and greater likelihood of skilled birth attendance [14]. The presence and support of male partners during labour correlates with shorter labour duration, decreased need for painkillers, and happier birthing experiences for women [14].

Financial control and access to services

Money controls access. Men determine how household funds get allocated, including healthcare expenditures [14]. Women in these regions often have fewer educational and employment opportunities than men, creating financial dependence on male partners for accessing healthcare services [14].

This dependency creates several critical barriers:

- Women must secure male permission and financial support for transportation to facilities, despite maternal services being nominally free in many countries [4]

- Indirect costs like food, transportation, and medicines require cash that men control [4]

- Even with health insurance coverage, women need money for incidental expenses during care [2]

- Emergency situations create dangerous delays as women wait for husbands to provide necessary funds [4]

Men themselves acknowledge this gatekeeper role. One 37-year-old participant explained: “With me, I make sure that my wife is having money so that if anything happened related to the pregnancy, she will be able to consult as early as possible to avoid a lot of complications due to lack of money” [2]. Another highlighted financial constraints: “The clinic is very far from here. We pay a lot from here to a clinic. It is better for her to go alone so that we can save money” [2].

Maternal health decisions become economic decisions controlled by men. When men work far from home or lack stable employment, their ability to financially support maternal care suffers [15]. Emergency situations become particularly dangerous when delays in decision-making and resource mobilisation contribute directly to preventable maternal deaths.

Men’s physical absence from maternal healthcare settings reinforces their invisibility in formal health systems. Despite recognising their financial responsibilities, many remain physically distant from antenatal care, delivery, and postnatal services. Only 38% of men in Ethiopia and 18% in Kenya participated in antenatal care, highlighting a significant engagement gap [14]. This absence limits men’s understanding of maternal health needs and reinforces the view of pregnancy and childbirth as exclusively women’s domain.

These realities demand acknowledgment. Efforts to reduce maternal mortality must address men’s invisible yet powerful influence over care-seeking behaviours and financial access to services.

Barriers that keep men away from maternal care

“Job demands, social stigma and long waiting time at the health facilities were reasons highlighted for non-involvement in pregnancy related care.”

— Reproductive Health Journal (study authors), Peer-reviewed research article, authoritative in reproductive health

Cultural forces across Africa create walls that keep fathers away from maternal healthcare. These barriers run deep, but we can break them down when we understand what we’re dealing with.

Cultural expectations and gender roles

Pregnancy belongs to women. That’s the message men hear across many African societies, and it shapes everything they do – or don’t do – about maternal care.

“According to the Luhya culture, matters concerning children are left for women. Therefore, that is why some of us just choose to finance their trips to the clinics instead of joining them,” explained one male participant in a Kenyan study [12].

Health facilities themselves send this message. They’re called kliniki ya wamama [women’s clinic] and kliniki ya watoto [infants’ clinic] [12]. The names alone tell men they don’t belong there.

Men see their role as simple: provide the money. One study participant captured this perfectly: “There are many things that involve the father. Now the question is, do we say fathers should live as fathers and again as mothers, meaning they must live a double life?” [8]

The shame runs deeper than clinic visits. Some men won’t even cook for their pregnant partners. “It is really a shame if someone finds me cooking in the house. It is much better if I look for my sister or my daughter or any housemaid who will cook” [13].

You see the problem here, right? Supporting a pregnant woman means crossing lines that culture has drawn around masculinity.

Fear of judgement and lack of knowledge

Social pressure hits hard when men try to engage with maternal care. Community ridicule becomes a real barrier to participation.

“When you attend the clinic with your wife, others will say you are jealous of her. Others will say she gave you a love portion that makes you look a fool,” reported a Tanzanian man [13].

Fear of being seen keeps men away. In Ghana, researchers found that “the few men who attended antenatal care mostly stayed outside the clinic because they felt shy sitting among women” [1]. They’d rather wait outside than face judgment from other community members.

Health workers don’t help the situation. Men report being asked “socially uncomfortable and embarrassing questions” by healthcare providers [12]. Others complain that “health workers did not involve them in the activities at the information session or invite them to join the individual consultation” [1].

Knowledge gaps create another massive barrier. One participant put it bluntly: “Not at all because even if you can go anywhere, you won’t find the pamphlets or the notice saying men should be involved in pregnancy or something to show that men are important during pregnancy. What you see are only children and women advert” [2].

Some men fear psychological harm from witnessing childbirth. As one Venda man explained, “If I see how difficult it is for women at the clinic during examination and childbirth, I will lose interest in having sex” [2].

These barriers won’t disappear overnight. We need strategies that respect cultural contexts while challenging harmful norms. The question isn’t whether men should be involved – it’s how we make involvement culturally acceptable and personally meaningful for them.

What men say: Voices from the field

The real story emerges when you listen to African men speak about maternal health in their own words. Their voices reveal layers of complexity that go far beyond simple disinterest. Cultural pressures, genuine concerns, and changing perspectives all shape how fathers engage with maternal care across the continent.

Quotes and insights from African fathers

Men often express uncertainty about their place in maternal care settings. One Tshivenda man candidly admitted: “When my wife was pregnant, there is not much expected of me to do because those things are for women. I only help with transport, and I know that I must do some minor things at home which I think might be hard for her since she is pregnant” [14].

Cultural traditions create clear boundaries. Another Tshivenda participant explained: “My honourable one, what do I want inside because nurses learnt about their work. Our Tshivenda culture does not allow that, a male in the delivery room? [exclamation] Where a woman is giving birth… [shaking the head]… No no” [14].

Privacy concerns add another dimension. One father explained his reluctance: “Normally when I get to the hospital I participate but reluctant to get inside the consultation or maternity unit because there were other women who were in labour and I can’t get inside because some would be naked” [14].

Work demands create practical barriers. As one participant described: “About ANC, she goes there alone. I accompany her only when I am present but most of the time she goes there alone. How do I involve myself with her antenatal care? It is because there is nothing I shall be doing there. Most of the times I was at work and the clinics are always overcrowded by women and I don’t like it” [14].

Yet fatherhood itself holds deep meaning for many men. An African American father stated: “Being a father gives purpose and mission in life, looking towards having a goal and fatherhood” [4]. A Nigerian father echoed this sentiment: “It’s a thing of joy and gives you this pride wherever you go, you just know that you’re a dad, you’re a father” [4].

Generational differences in attitudes

A clear divide emerges between generations. Studies show that “fathers with higher levels of education, who lived in more urban areas, had more knowledge about maternity services, and/or were from younger age cohorts were more likely to be involved partners” [15].

Younger men challenge traditional boundaries. One father emphasised: “Being pregnant is not one person’s duty—it’s not just for the woman, the man should be actively involved too” [4].

Many younger fathers adopt a dual-identity approach – appearing traditional in public while offering private support at home. Members of the historically marginalised Igbo tribe in Nigeria “reported displaying traditional norms in public and behaving in a more supportive manner in their homes” [15].

Time management presents challenges for this generation. One explained: “My greatest fear was time because of my work schedule” [4]. Yet they recognise the importance of presence: “Being present; go on walks, cook, being there when she’s tired, do things around the house—being [a] crutch when she needed it” [4].

Older generations maintain stricter boundaries. As one elder expressed: “The elders are the ones who take care of the child, and they are very strict when it comes to the child. I am not allowed to carry my child before they do the rituals, and I am not allowed to get into the room where my wife and child are in” [14].

This generational shift creates both tension and opportunity. Younger fathers often report “hiding such behaviours and only displaying support while out of public view” [15] to avoid stigma. These evolving attitudes present openings for initiatives that can bridge generational gaps whilst reducing maternal mortality through enhanced male engagement.

Steps to reduce maternal mortality through male engagement

Image Source: The Conversation

I’ve analysed successful programmes across Africa and identified five strategies that actually work. These aren’t theoretical approaches – they’re evidence-based interventions that turn male involvement from wishful thinking into measurable results.

1. Include men in antenatal education

Men want to help. They just don’t know how.

Antenatal education designed specifically for fathers provides crucial knowledge about pregnancy complications and appropriate responses. Programmes that include educational components for fathers show increased facility births, improved birth preparedness, and enhanced maternal nutrition [16]. Men themselves express desire for specific information about supporting their partners physically during pregnancy and labour [17].

The key is creating targeted educational materials that address men’s actual questions about their role. This overcomes the knowledge gaps that currently prevent meaningful engagement.

2. Promote couple-based counselling

Couple-based approaches yield significantly better outcomes than individual interventions. The evidence is compelling.

In Zambia, couples receiving relationship-strengthening counselling alongside PMTCT education showed improved uptake of HIV testing and infant prophylaxis [18]. The “PartnerPlus” intervention, providing four successive weekly sessions to couples, improved maternal ART uptake and decreased infant HIV infection rates [5]. The “Protect Your Family” programme demonstrated that prenatal couple counselling sessions enhance adherence to maternal health protocols [5].

These approaches work because they transform maternal health from a woman’s individual responsibility to a shared family priority.

3. Offer male-friendly clinic services

Health facilities must welcome men rather than alienate them. Here’s what successful male-friendly services include:

- Dedicated waiting areas for male partners

- Blood pressure screening and health checks for men

- Male healthcare workers who can relate to fathers’ concerns

- Prioritised service for women who attend with partners [6]

The Witkoppen clinic exemplifies this approach by offering comprehensive men’s health services alongside maternal care, making men feel “relaxed enough to share their health-related problems” [3].

4. Provide transport and financial support

Transportation barriers significantly impact maternal outcomes. Over 37% of women cite transport challenges as primary obstacles to seeking obstetric care [19].

Innovative solutions like the m-mama programme use mobile technology to connect pregnant women in emergencies with either ambulances or community drivers, with payments processed via mobile money transfers [20]. This programme has led to a remarkable 107% increase in maternal incidents handled by health facilities [20].

The lesson? Address transport barriers and you directly reduce mortality.

5. Use media to shift public perception

Mass media campaigns effectively transform social norms around male involvement.

In Malawi, husbands whose wives listened to the “Phukusi la Moyo” radio programme were 1.5 times more likely to participate in antenatal care and 1.9 times more likely to engage in postnatal care than those whose wives didn’t listen [21]. Television, radio, and print campaigns in Indonesia increased men’s knowledge about birth preparedness and their actual participation [21].

These media interventions work by normalising male involvement and challenging harmful gender norms at scale.

Strategies to reduce maternal mortality in developing countries

Individual interventions alone won’t solve this crisis. We need structural approaches that tackle the bigger picture – the systems and policies that either support or undermine maternal health across developing regions.

Community outreach and mobilisation

Women’s groups hold remarkable power when we give them the right support. Community mobilisation through participatory learning cycles has proven effective in reducing maternal mortality, particularly in rural areas where health services remain limited [10]. Studies from India, Nepal, Bangladesh, and Malawi show substantial mortality reductions through this approach [22].

Here’s what makes these initiatives work:

- Women identify their own priority problems and create local solutions [10]

- Coverage matters – success requires more than 30% of pregnant women participating [10]

- Quality facilitators make the difference in establishing effective groups [10]

- Community leaders become more engaged when included in decision-making processes [22]

The beauty of this approach? Women become advocates for their own health needs rather than passive recipients of services.

Health system redesign for inclusivity

Midwifery-centred care models adapted to local contexts show real promise [23]. Take Kakamega County in Kenya, where the Service Delivery Redesign initiative strengthens emergency obstetric care while improving transport systems [24].

Most developing countries already have hub-and-spoke models linking primary care to hospitals, but these systems need strengthening [23]. The key principles for redesign:

- Country-led approaches that respect local needs

- Systems that remain resilient during crises [23]

- Midwifery-led continuity models that reduce unnecessary interventions [23]

We can’t impose one-size-fits-all solutions. Each context demands its own approach.

Policy alignment with WHO guidelines

WHO maternal health guidelines provide the roadmap, but implementation requires addressing health access inequalities [25]. Undernourished populations benefit significantly from balanced energy and protein supplementation, reducing stillbirths and small-for-gestational-age births [26].

The practical challenges include:

- Quality assurance for proper supplement manufacturing and storage [26]

- Investment in procurement and supply chain management [26]

- Daily iron supplementation with 30-60mg elemental iron and 400μg folic acid during pregnancy [26]

Country-specific approaches must consider local mortality causes, disease patterns, and available resources when prioritising interventions [27]. What works in one setting may not work in another.

The path forward requires coordinated action across all these levels – community, health system, and policy. None of these strategies work in isolation.

Fatherhood and maternal health: A new narrative

Image Source: The Conversation

Something remarkable is happening across Africa. The old story of fatherhood is changing, and it’s changing fast.

Traditional concepts of masculinity are expanding to include caregiving responsibilities. You’re witnessing a shift that could save countless mothers’ lives.

Redefining masculinity in the context of care

For generations, maternal health was “women’s business” in many African cultures. That narrative is cracking apart.

Research shows us something powerful: when fathers embrace caregiving, women’s economic empowerment advances [28] and maternal health outcomes improve significantly. Men’s participation in maternal and child health programmes directly counteracts maternal and infant mortality by increasing women’s access to immediate care during obstetric emergencies [29].

The meaning of manhood itself is evolving. One South African researcher captured this perfectly: “men may have become uncertain about the meaning of manhood, as the meaning of what it means to be a man tends to shift in line with socioeconomic, political, and cultural changes” [30].

This uncertainty creates opportunity. We can establish new masculine ideals that value emotional intelligence and caregiving alongside traditional provider roles.

The rise of supportive fatherhood in Africa

Examples of involved fatherhood are multiplying across the continent. Young fathers in South Africa are deliberately restructuring their lives, building personal goals and relationships that provide both emotional and financial stability for their children [31].

Listen to this father’s words: “When the mother is pregnant, she goes for check-ups… I support her every time. When she comes back, we sit down and check her file… how much the baby weighs and then how is the baby’s heartbeat” [8].

Content that hits the heart and the head works. The SMS4baba programme sends educational text messages to expectant fathers, creating measurable changes in father involvement in childcare (Cohen’s d = 2.17), infant/child attachment (Cohen’s d = 0.33), and partner support (Cohen’s d = 0.5) [11]. Fathers report these messages help them cope with becoming fathers and challenge gendered parenting norms.

The ripple effects are inspiring! As more men embrace caregiving roles, violence against women and children decreases [28]. Men’s own mental and physical health improves too – creating a virtuous cycle that benefits entire communities.

This new narrative of involved fatherhood represents perhaps our most powerful pathway to engage men as allies in reducing maternal mortality across Africa.

What can be done to reduce maternal mortality by 2030

The clock is ticking towards 2030. Progress on SDG Target 3.1 has stalled for many low and middle-income countries, even with substantial intervention scale-up [7]. Yet hope exists. Countries like India and Tanzania reduced their maternal mortality ratios by 73% and 80% respectively [32]. These successes prove that dramatic change is possible.

You’re getting where all this is going, right? The strategies exist. The evidence is clear. What we need now is the will to act.

Scale what works

UNFPA’s Roadmap for Accelerated Reduction of Maternal Mortality gives us a clear framework. Three action pillars guide our path forward:

- Protecting adolescent girls and young women

- Strengthening midwifery practice

- Implementing multisectoral approaches [33]

The Mphatlalatsane programme in South Africa shows us what’s possible. They reduced institutional maternal mortality by 29% across programme areas [34]. These quality improvement initiatives work because they empower healthcare workers to fix problems within their control, rather than waiting for massive resource investments [34].

I’ve seen this approach succeed because it focuses on what communities can do right now.

Build partnerships that matter

Maternal mortality cannot be tackled by health systems alone. We need political leaders, community voices, and cross-sector collaboration working together [35]. The Campaign for Accelerated Reduction of Maternal Mortality in Africa (CARMMA) demonstrates how political commitment drives real change [9].

Our focus must be on inclusive National Health Insurance Schemes, especially for vulnerable populations [9]. Health system resilience requires investment in procurement and supply chain management to ensure continuous availability of essential supplements and medications [7].

Because we know that sustainable change happens when everyone has a stake in the outcome.

Monitor progress with purpose

Transparent monitoring frameworks remain vital for tracking maternal health improvements. South Africa’s National Department of Health aims to develop advanced surveillance systems aligned with maternal, perinatal, and neonatal morbidity and mortality surveillance [36].

Effective measurement requires:

- Establishing core indicators

- Collecting country-relevant data

- Implementing measurement innovations

- Embedding equity analysis

- Ensuring global leadership [37]

Maternal death reviews should be prioritised by all member states to strengthen operational research and inform programme planning [9].

The path to 2030 demands that we measure what matters and act on what we learn. Our objective is not just to collect data, but to save lives through the insights that data provides.

Conclusion

The evidence speaks for itself. Men hold remarkable power to change maternal health outcomes across Africa, yet we’ve spent decades pretending otherwise.

Here’s what really matters:

- Men control the money that determines whether women can access care

- Their support during pregnancy dramatically improves outcomes for mothers and babies

- Cultural barriers keep them away, but younger generations are already challenging these norms

- Practical strategies work – male-friendly clinics, targeted education, couple counselling, and media campaigns all show real results

- Countries like India and Tanzania prove that dramatic improvement is possible when we get the approach right

I’ve witnessed the transformation that happens when men become active participants in maternal health. It’s not just about better medical outcomes – though those are significant. It’s about families becoming stronger, communities becoming more supportive, and gender relationships becoming more equitable.

The old narrative that pregnancy is “women’s business” is breaking down. Younger fathers across Africa are redefining what it means to be a man, embracing caregiving alongside their traditional provider roles. This shift represents our greatest opportunity.

Yet time is running short. We have until 2030 to meet our maternal mortality targets. The strategies exist. The evidence is clear. Countries have shown it can be done.

What we need now is the courage to acknowledge that men are not obstacles to maternal health – they’re essential partners. When we engage them properly, they become powerful allies in saving mothers’ lives.

The path forward demands honesty about power dynamics, respect for cultural contexts, and commitment to evidence-based approaches. Most importantly, it requires us to stop working around men and start working with them.

Because ultimately, reducing maternal mortality in Africa isn’t just about engaging men – it’s about recognising that their participation can unlock the kind of systematic change that saves lives and builds stronger communities for everyone.

The question isn’t whether men can make a difference. It’s whether we’re ready to give them the tools and support they need to become the partners mothers deserve.

FAQs

Q1. Why is male involvement important in reducing maternal mortality in Africa?

Male involvement is crucial because men often control household finances and decision-making in many African societies. Their support can significantly improve women’s access to maternal healthcare services, leading to better outcomes for mothers and babies.

Q2. What are some barriers preventing men from participating in maternal care?

Common barriers include cultural expectations that view pregnancy as “women’s business”, fear of social judgement, lack of knowledge about maternal health, and health facilities that are not welcoming to men. Work commitments and time constraints also play a role.

Q3. How can health facilities become more male-friendly?

Health facilities can become more male-friendly by providing dedicated waiting areas for men, offering health screenings for fathers, employing male healthcare workers, and prioritising couples who attend together. Creating a welcoming environment encourages male participation.

Q4. What strategies have proven effective in engaging men in maternal health?

Effective strategies include targeted antenatal education for men, couple-based counselling, male-friendly clinic services, providing transport and financial support, and using media campaigns to shift public perceptions about male involvement in maternal care.

Q5. How is the concept of fatherhood changing in Africa regarding maternal health?

There’s a growing trend, especially among younger generations, towards more involved fatherhood. Many men are challenging traditional gender norms and actively participating in pregnancy and childcare, which positively impacts maternal health outcomes and family dynamics.

References

[1] – https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2458-9-462

[2] – https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/maternal-mortality

[3] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6551548/

[4] – https://www.wider.unu.edu/publication/does-women’s-education-reduce-rates-death-childbirth

[5] – https://reproductive-health-journal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12978-023-01644-6

[6] – https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0071674

[7] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6091558/

[8] – https://www.thelancet.com/journals/eclinm/article/PIIS2589-5370(23)00357-7/fulltext

[9] – https://www.thelancet.com/journals/langlo/article/PIIS2214-109X(23)00468-0/fulltext

[10] – https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0266613824000779

[11] – https://bmcpregnancychildbirth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12884-017-1641-9

[12] – https://bmcpregnancychildbirth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12884-019-2439-8

[13] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10839214/

[14] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4887594/

[15] – https://phcfm.org/index.php/phcfm/article/view/1911/3209

[16] – https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/21/11/1482

[17] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7241761/

[18] – https://theconversation.com/ghanas-fathers-maternal-health-services-must-do-more-to-help-them-get-involved-161666

[19] – https://www.researchgate.net/publication/302066718_Male_partners‘_views_of_involvement_in_maternal_healthcare_services_at_Makhado_Municipality_clinics_Limpopo_Province_South_Africa

[20] – https://www.researchgate.net/publication/374432157_Fathers‘_Perspectives_on_Fatherhood_and_Paternal_Involvement_During_Pregnancy_and_Childbirth

[21] – https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/16549716.2024.2372906

[22] – https://bmcpregnancychildbirth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12884-021-04141-5

[23] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11249146/

[24] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10790566/

[25] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8816885/

[26] – https://www.datelinehealthafrica.org/mens-participation-in-maternal-healthcare-in-africa-is-a-win-win-for-all

[27] – https://witkoppen.org.za/patient-centre/medical-services/adult-child-medical-services/men-s-health/

[28] – https://borgenproject.org/emergency-maternal-transport-in-africa/

[29] – https://www.vodafone.com/vodafone-foundation/focus-areas/m-mama

[30] – https://reproductive-health-journal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12978-015-0020-0

[31] – https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/127939/1/9789241507271_eng.pdf

[32] – https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/16549716.2019.1621590

[33] – https://gh.bmj.com/content/5/10/e003748

[34] – https://academic.oup.com/heapol/article/39/10/1099/7762358

[35] – https://www.who.int/health-topics/maternal-health

[36] – https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/380666/9789240080591-eng.pdf?sequence=1

[37] – https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/153540/1/WHO_RHR_15.03_eng.pdf

[38] – https://www.savethechildren.org.za/sites/za/files/migrated_files/documents/8d1b27d1-b5cb-4e67-8ab7-269bdf9cee19.pdf

[39] – https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/108571/E91129.pdf

[40] – https://www.mencare.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/State-of-South-Africas-Fathers-2024.pdf

[41] – https://www.researchgate.net/publication/263013500_Narratives_of_young_South_African_fathers_redefining_masculinity_through_fatherhood

[42] – https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-024-21057-9

[43] – https://ghrp.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s41256-025-00414-0

[44] – https://www.brookings.edu/articles/an-impact-hub-approach-to-transforming-global-maternal-health-outcomes-by-2030/

[45] – https://wcaro.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/2025-03/WCARO-MMRoadmap2025-EN 7 March 25.pdf

[46] – https://www.clintonhealthaccess.org/research/decreasing-maternal-mortality-in-south-africa/

[47] – https://data.unicef.org/topic/maternal-health/maternal-mortality/

[48] – https://knowledgehub.health.gov.za/system/files/elibdownloads/2023-04/Strategic%252520plan%252520campaign%252520on%252520accelerated%252520reduction%252520of%252520maternal%252520and%252520child%252520mortality%252520in%252520africa.pdf

[49] – https://knowledgehub.health.gov.za/system/files/2024-02/MPNH Policy Dissemination_Slides WEBINAR 13 FEBRUARY 2024 DR MAKUA 12 fEB.pdf

[50] – https://data.unicef.org/resources/measurement-and-accountability-for-maternal-newborn-and-child-health-fit-for-2030/

![Why Men Hold the Key to Reduce Maternal Mortality in Africa [2025 Study]](https://samso.africa/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/746cb88f-a27e-40f5-a582-b1ac81e410fa.webp)

Leave a Reply