Shortly after our wedding, Mia and I found ourselves yearning for an international adventure. Our relationship had blossomed amidst travels – we got engaged in the vibrant streets of Brazil and celebrated our honeymoon in the bustling metropolis of Hong Kong.

Whilst these journeys were captivating, we sought something more profound, an experience that would delve deeper than the typical tourist encounters.

We discovered VSO Canada, an overseas placement organisation whose mission resonated with our desire to make a meaningful impact. Their commitment to fostering skill-sharing, creative exchange, and mutual learning to create a more equitable world aligned perfectly with our values.

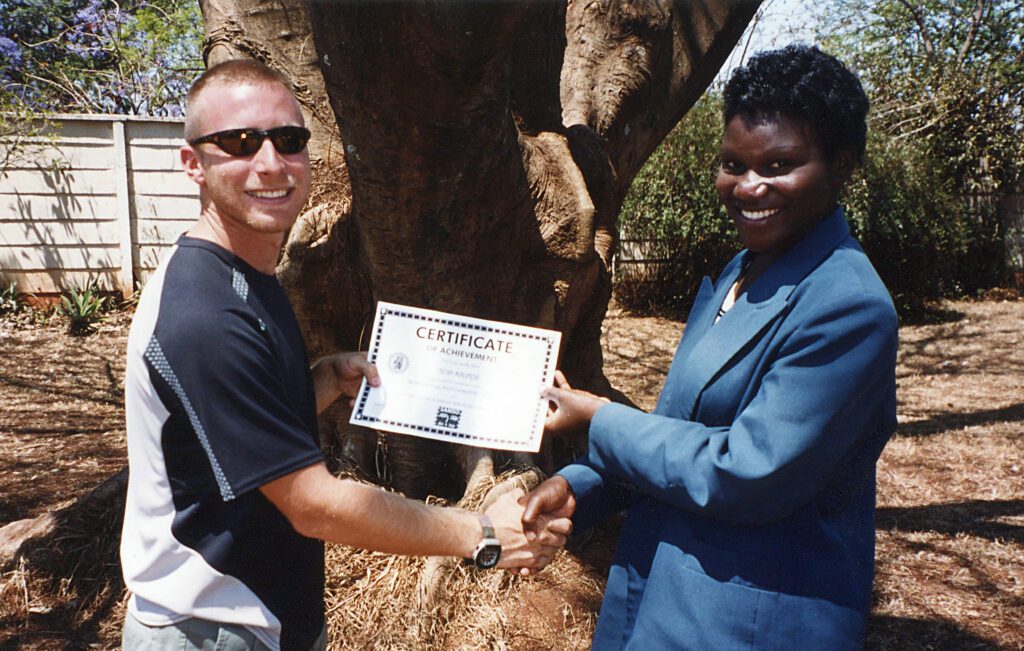

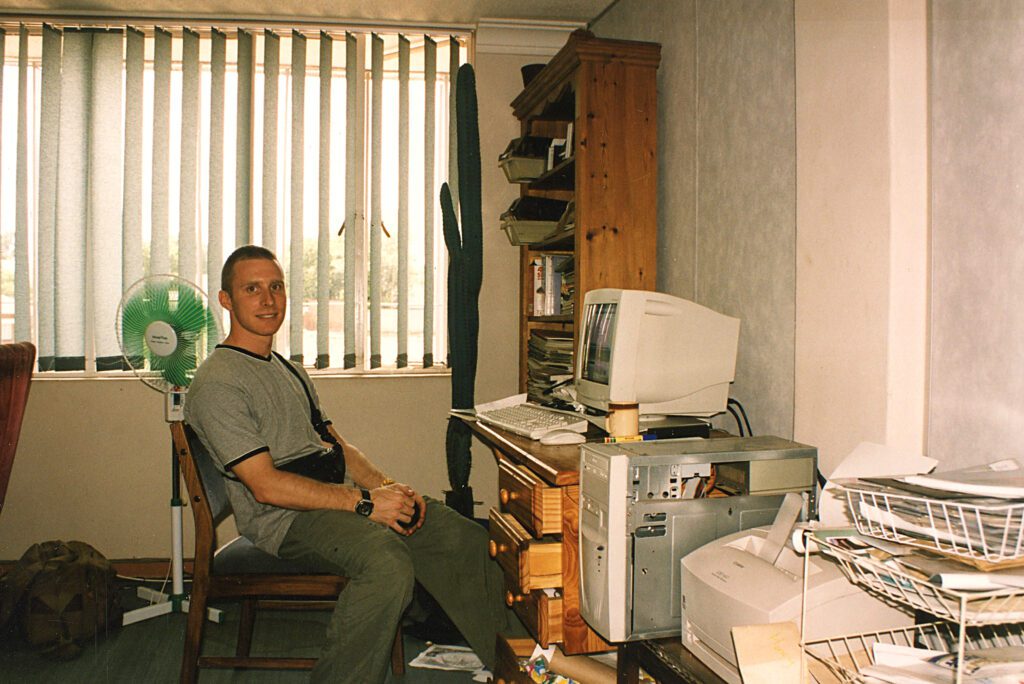

Mia’s expertise as a physiotherapist opened doors to numerous global opportunities. My path as an artist photographer, however, led to a singular yet intriguing prospect in Zimbabwe with SAMSO (Southern Africa Media Services Organization), where I would serve as both photographer and trainer.

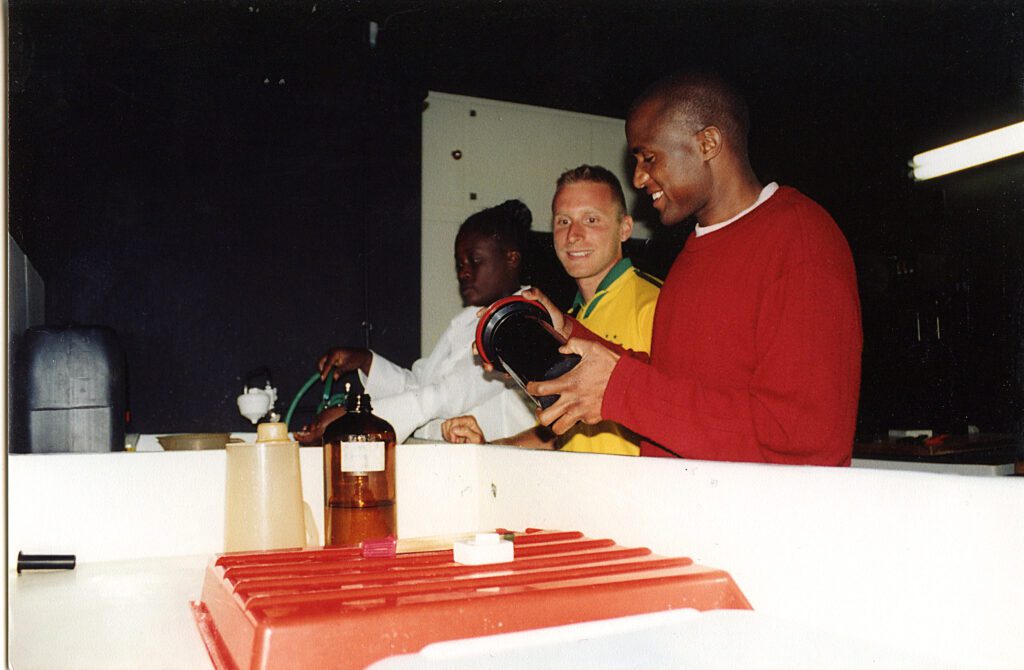

The position description remains etched in my memory: “We seek an experienced photographer to collaborate with and mentor photojournalists across Southern Africa. The ideal candidate must demonstrate adaptability and resilience, including the ability to process films in makeshift conditions, such as hotel bathrooms.”

Upon reading this, I knew instinctively that this was my calling. Fortuitously, Mia secured a physiotherapy position in the same city, enabling us to commit to a two-year journey of living and working in Zimbabwe.

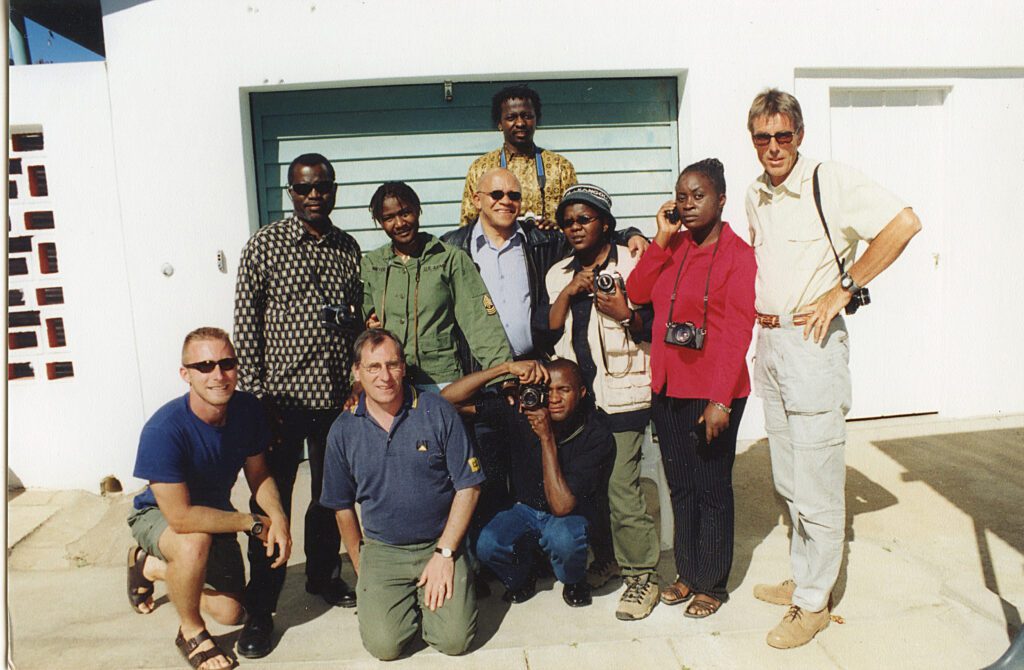

During the 30-hour flight, I thought about what unique perspective I could bring as a young white Canadian artist to the group of experienced Southern African journalists. However, upon arrival, I swiftly discovered that this experience would evolve into a genuine two-way exchange of knowledge and culture.

The most prominent challenges revolved around visual storytelling techniques. Zimbabwe’s rich oral tradition had fostered strong written communication skills, and the technical aspects of camera operation were impressively mastered.

However, the art of crafting narratives through imagery remained an area for development. In Canada, we often take for granted our immersion in powerful visual storytelling.

This constant exposure naturally cultivates an intuitive understanding of what constitutes a compelling image amongst the general population. The limited access to diverse, high-quality visual references had impacted the development of visual literacy skills.

My role centred on nurturing these capabilities and encouraging the creation of photo narratives. In return, my colleagues imparted invaluable investigative journalism techniques that enhanced both my writing and photographic practice.

My experience of Zimbabwe stood in stark contrast to its portrayal in Western media, which became a significant point of discussion.

I observed that Africa’s narrative was predominantly controlled by a select few major Western news organisations. This observation, whilst potentially cynical, was reinforced after meeting numerous journalists from these outlets.

Many had predetermined their stories before arriving, merely seeking images to support their preconceived narratives during brief visits.

This realisation validated SAMSO’s mission to amplify African journalists’ voices. After all, who could better articulate Africa’s stories than those with deep-rooted understanding of local contexts and nuances?

Reconciling my position as a Western photographer whilst advocating for African photographers’ agency required considerable reflection. Ultimately, my approach centred on intention.

Photography has always been my tool for making sense of the world around me. If my images, created in pursuit of deeper understanding, can contribute to shifting perceptions and challenging preconceptions, I welcome that outcome.

Unlike those brief parachute assignments, I invested significant time in comprehending complex issues, always mindful not to position myself as the definitive voice on these matters.

When viewers encounter my photographs, they frequently enquire about the technical aspects of capturing such striking images. This perspective troubles me, as I draw a clear distinction between merely taking photographs and thoughtfully creating them.

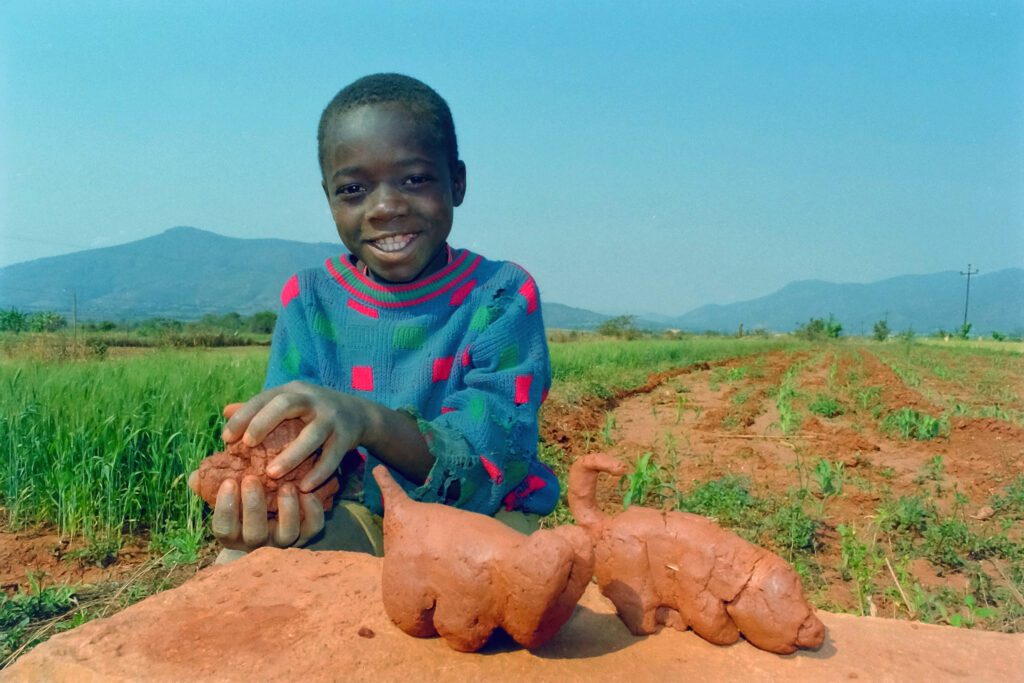

The notion of taking pictures implies a focus on technical proficiency and compositional strategies to achieve aesthetic appeal. My work, however, emerges not from a desire to create visually pleasing images, but from a genuine fascination with human beings and their interactions with their environment.

In my earlier work, when I concentrated solely on producing aesthetically pleasing images, the results often lacked depth and resonance, reflecting my superficial engagement with the subject matter.

Throughout my journeys, I’ve come to deeply value the gift that each photograph represents from those I encounter.

Accordingly, I express my gratitude as I would for any meaningful gift. I make every effort to share prints with my subjects.

In situations where formal addresses aren’t available, I arrange to leave images at local gathering points – shops, religious centres, or educational institutions – designating community representatives to facilitate distribution.

For many individuals in remote locations, these photographs often represent their only family portraits.

This practice also helps maintain positive relationships between photographers and communities, considering our role as ambassadors for the profession globally.

Nothing could be more detrimental to the trust between subject and photographer than those who practice ‘shoot-and-run’ photography.

To explore more of Terry Pidsadny’s work, visit www.pidsadny.com.

Leave a Reply